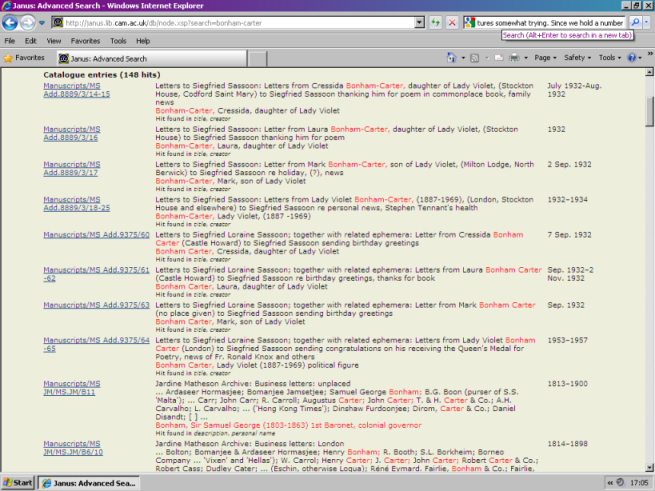

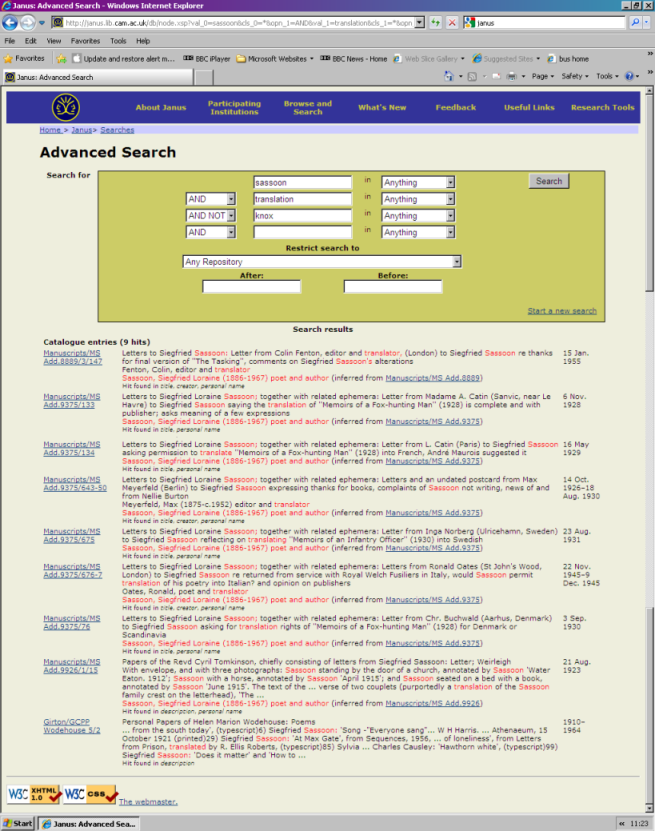

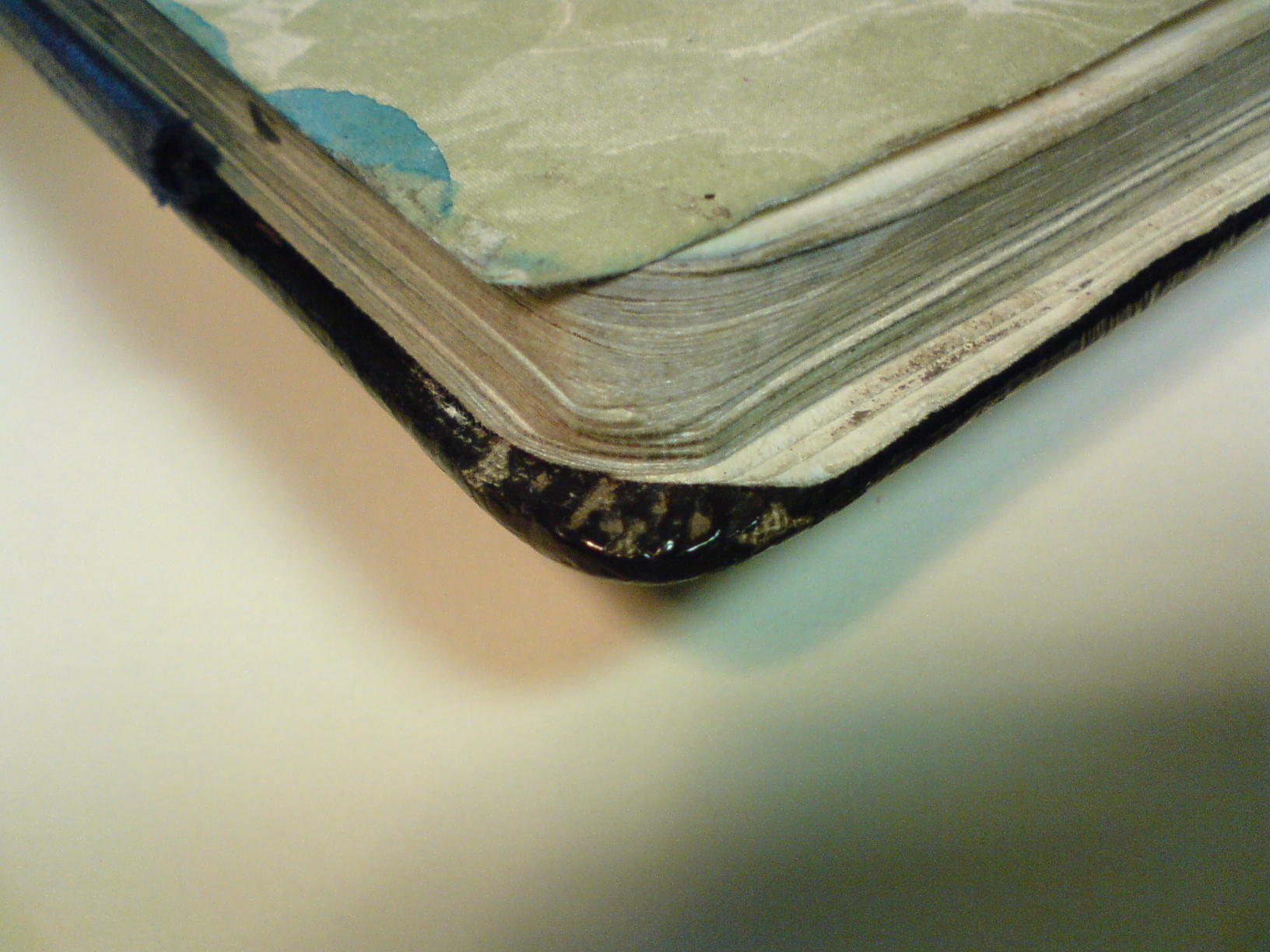

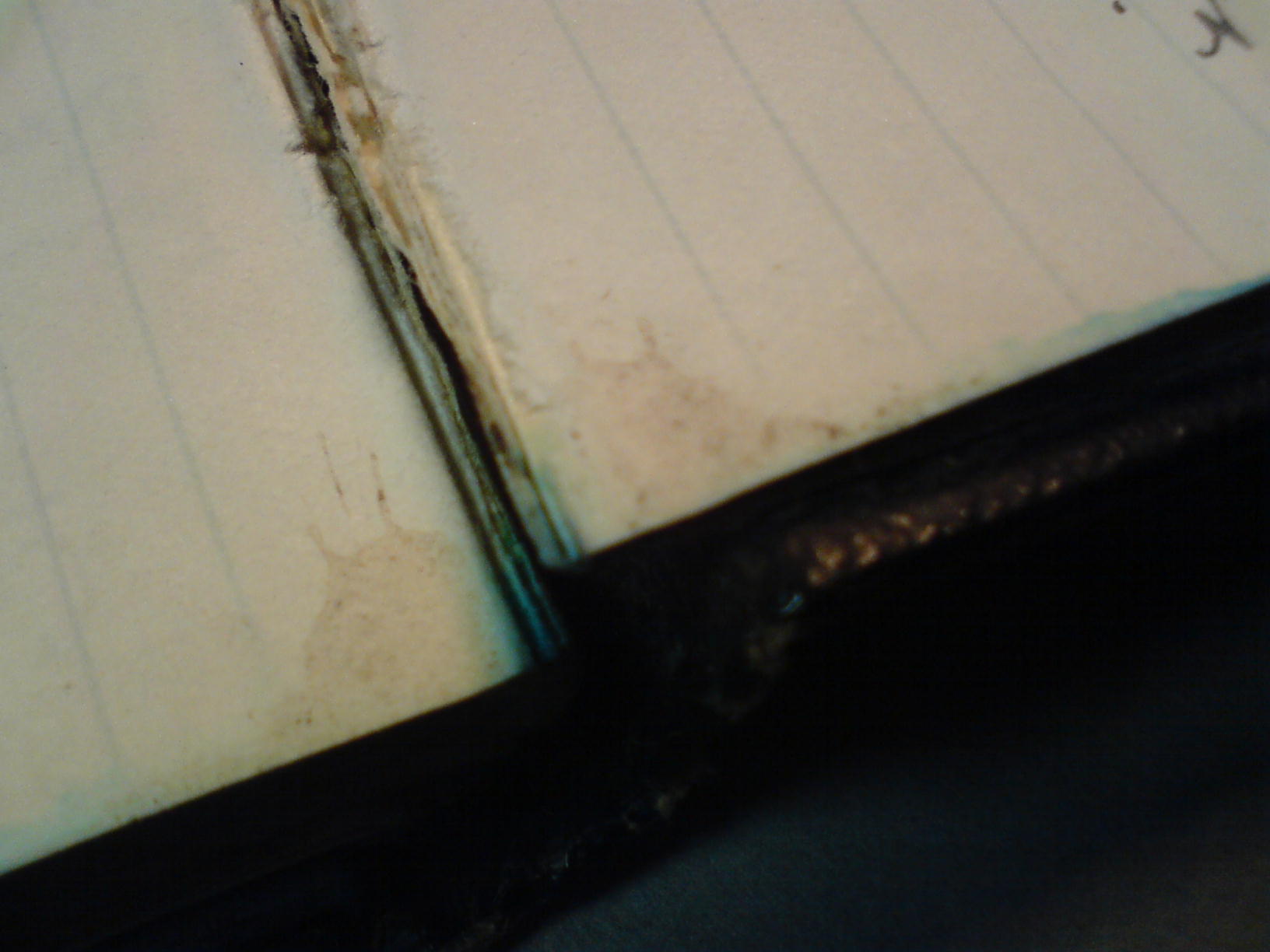

I am currently in the process of foliating Siegfried Sassoon’s journals. By ‘foliating’ I mean I am writing a running number on the top right corner of every two facing pages in each volume. This, as you might well imagine, is a time consuming process but we consider it worthwhile for a number of reasons: the improvement of document security; the ease of providing precise references for quotations; and allowing accurate recoding of the original location of loose enclosures. I am removing the enclosures to be stored unfolded in separate files.

It occurred to me, after reading my colleague Megan’s interesting posting on Valentine’s cards on the Tower Project Blog, to wonder what Sassoon thought of such items. I present below outlines of Sassoon’s journal entries for 14 February during his love affair with the aesthete Stephen Tennant. Whilst I did not find a clear answer to my question what I did find is never-the-less I think of interest:

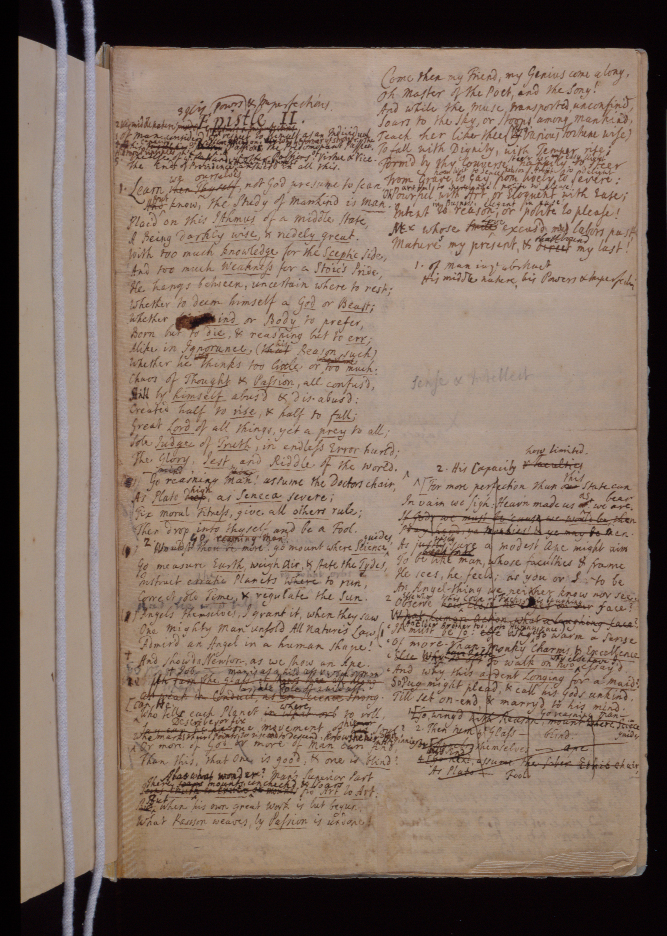

MS Add.9852/1/27

Entry for 15 February 1928

Sassoon was in the process of writing A Fox Hunting Man. Tennant, with whom he had begun a clandestine love affair in the previous summer, had gone to the Continent. Sassoon received a cable from his more openly acknowledged lover Glen Byam Shaw (who was away working in New York). William Walton visit him and Sassoon paid him £20 to help Walton travel to be with Tennant. He also entreated him to explain to Tennant that he would not be joining them unless began to suffer writer’s block with work on his book. Sassoon was pleased with his writing progress and had been noting how many words a day he was writing. He went to a classical concert on the night of 14 and makes no mention of Valentine’s sent or received.

MS Add.9852/1/28

Entries on and around 14 February 1929

Sassoon was in London and was socialising with Glen Byam Shaw who had returned from America with a new lover of his own, Angela Baddeley. Sassoon was basking in the news of winning a literary prize. On the 14 itself he dined with Glen Byam Shaw at the Ken[sington] Hotel and they talked until late. No mention is made of Tennant or St Valentine, although elsewhere Sassoon admits his infatuation for Tennant.

MS Add.9852/1/30

11 & 17 February 1930

Sassoon was away in Sicily with Tennant but Sassoon had been unwell and was in bed for over a week. He was however still working (writing). Tennant, who by now, was under a course of treatment for consumption (tuberculosis) had been collecting shells and Sassoon talks romantically of him but does not mention St Valentine’s day.

MS Add.9852/1/31

14 February 1931

By this date Tennant had become very ill and reclusive and although Sassoon felt badly treated by Tennant’s rejection he was not yet willing to ‘condemn’ their relationship. On the night of the 13 Sassoon was staying overnight at a hotel near Tennant’s home, Wilsford. On the morning of the 14 Sassoon went to Wilsford without phoning ahead and disturbed Tennant by standing at his window and looking in on him in his sick bed. Tennant’s light mood angered Sassoon and he parted from him sullenly and felt guilty for the rest of the day. He described his subsequent early spring drive from Wiltshire to Kent delightfully but ended it with a whistful remark about St Valentine’s day. He was so out of sorts by the time he reached his mother’s home that he could not even bring himself to tell her about his newly purchased horse.

MS Add.9852/1/35

13 & 14 February 1932

Sassoon took a house (Fitz House) close to Tennant’s home at Wilsford. The journal for this period contains reams of introspective diary entries as Tennant who was often still unwell was refusing to see visitors because of his consumptive appearance. On the night of the 13 Sassoon agonised about whether to send him a Valentine’s greeting as he craved Tennant’s attention but did not wish to condone his behaviour. The following day he was curiously reassured when the Hunter sisters (gardeners at Wilsford) came to tell Sassoon that a chimney fire in Tennant’s room had allowed his nurse to insist they remove him to his library and spring clean his room.

MS Add.9852/1/36

Retrospective entries from 19 February 1933

Although relations between Sassoon and Tennant had improved by 1933 Sassoon spent the 14 riding out alone and working on the writing of Sherstone. On the 15 he called on Tennant but makes little of it being rather preoccupied by motoring accident with a bus.

It seems, admittedly on rather sparse evidence, that Valentine’s day seemed to mean the most to Sassoon in the years when his relationship was at its lowest ebb. It would be a most interesting exercise to extend this Valentine’s search across the full journal series.