Motorbikes

We’re coming to the end of writing the exhibit captions for the ‘Dream Voices’ exhibition. We try not to let the captions go too far over a hundred words each: if we exceeded that limit too often, a display with fifty or sixty exhibits (most of which are themselves written texts) would present an exhausting amount of reading.

I don’t always find it possible to be as concise as I would like. Each caption represents a mini-research exercise, and following the leads through printed reference works and web-based resources often turns up a great deal of interesting detail that will never make its way into the final text. A caption is there to identify the exhibit, place it in context, and perhaps indicate one or two points of interest that might otherwise be missed: perhaps explaining a technical term or identifying a named individual.

A recent caption drew me into some unfamiliar by-ways. One of the items received with the newly-accessioned Sassoon Archive (MS Add. 9852) is a notebook used by Sassoon to record cricket matches in which he took part between 1899 and 1905. Most of the matches recorded were played in Kent during his school holidays, when Sassoon turned out for local village sides or for scratch elevens assembled by his brother Michael or himself. Several of the matches were played for an ‘I. B. Hart-Davies XI’, and as the most attractive opening of the book to display in the exhibition had details of one of these matches, I wanted to find out more about the captain of this side.

It transpired that Hart-Davies was a well-known figure in the early history of motorcycling. After attending the King’s School in Canterbury he had become a schoolmaster at the New Beacon in Sevenoaks, which the Sassoon brothers attended (and is described by Siegfried in the first chapter of ‘Seven More Years’, the second part of The Old Century). In 1909, Hart-Davies took the motorcycle speed record between John o’ Groats and Land’s End, covering 886 miles in 33 hours and 22 minutes. The motorcycling journalist ‘Ixion’ (pen-name of Basil H. Davies) remembered that although he wasn’t the fastest rider over short courses, Hart-Davies’s physical stamina was ‘colossal… he never tired.’ In 1911 he reduced the John o’ Groats to Land’s End record to 29 hours 12 minutes, but this was his last attempt: according to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, ‘As his speed exceeded the then maximum of 20mph further official record attempts were banned by the Auto Cycle Union.’

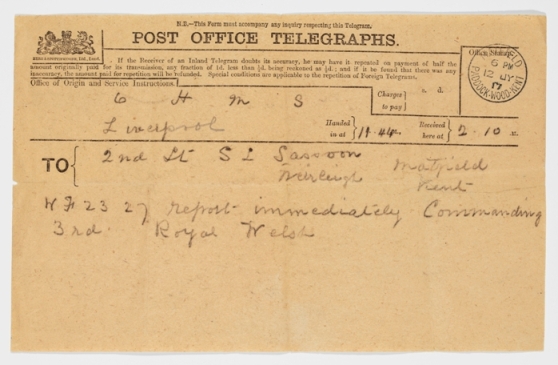

After giving up school-teaching Hart-Davies became an insurance broker in the Midlands. In 1913 he qualified as a pilot, and it was rumoured that he took up flying to try to set another John o’ Groats to Land’s End speed record, by air. However, it was flying that led to his death: he was killed in July 1917 on a training flight as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps. An obituary notice in The Times recorded that, with three other motorcyclists, he won the Mürren Cup, despite the fact that none of the team had ever done any bobsleighing before. A fellow-officer quoted by The Times called Hart-Davis a ‘gallant fellow whom we all liked immensely’.

The King’s School in Canterbury, which has undertaken research on its Old Boys killed in the War, knew about Hart-Davies’s motorcycling exploits, but hadn’t heard of his cricket XI or his links with Sassoon. Among the huge research potential of the Cambridge Sassoon Archive, a cricket scorebook may represent only a tiny part; but nevertheless this document gives us a previously-unseen glimpse of the unusually active sporting life of one of the generation heading unknowingly to war.