An audio file of Alison Hennegan’s talk entitled ‘A War Poet in the Making?: Siegfried Sassoon’s Pre-War Writings’, which formed part of this year’s Festival of Ideas, is available here: <http://sms.cam.ac.uk/media/1078104>. We are grateful to Alison for her talk, and to the Sassoon estate for permission to use the quotations from the writings of Siegfried Sassoon. The file will be accessible until 1 February 2011.

Alison’s talk was complemented by a small display of Sassoon’s juvenilia. Here are the captions:

The Cambridge Review

Vol. XXVII, No. 678, 15 March 1906

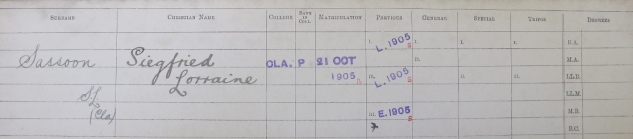

Sassoon’s career as a published poet began in April 1903 with the first in a series of five poems printed in the journal Cricket. ‘To a “Blood”’ was Sassoon’s earliest appearance in a Cambridge periodical, achieved in his first year at Clare College. The last line is University jargon: the ‘Little go’ was the popular name for the ‘Previous Examination’, the first examination for the Bachelor of Arts degree, and to ‘plough’ is to fail an examination.

Cam.b.41.30.27

*

The Granta

Vol. XIX, Special May Week Number 1906

‘The Bomb’, a dramatic monologue mimicking the style of Robert Browning, was the last poem by Sassoon to appear in a Cambridge periodical until his war verse began to be published in the Cambridge Magazine in 1916. The poem imagines an attempted assassination similar to the plot which was to kill Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in 1914 and lead directly to the outbreak of the First World War.

Cam.b.41.16.18

*

Poems

1906

This was Sassoon’s earliest collection of poetry, privately printed for him by J. E. Francis & Co. in the autumn of 1906. In his memoir The Old Century and Seven More Years (1938), Sassoon recorded that the epigraph from Swinburne on the title-page ‘expressed an exuberant belief in my poetic vocation’. He also wrote there that the paper used for the edition ‘was poor, and has since shown a tendency to break out into small yellow spots like iron mould.’ This fate has indeed overtaken the University Library’s copy.

Keynes.J.1.12

*

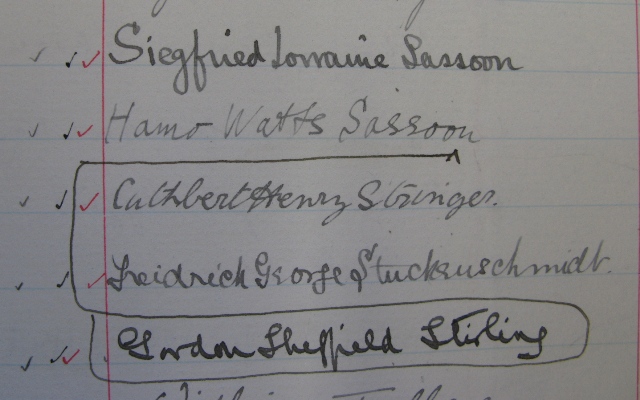

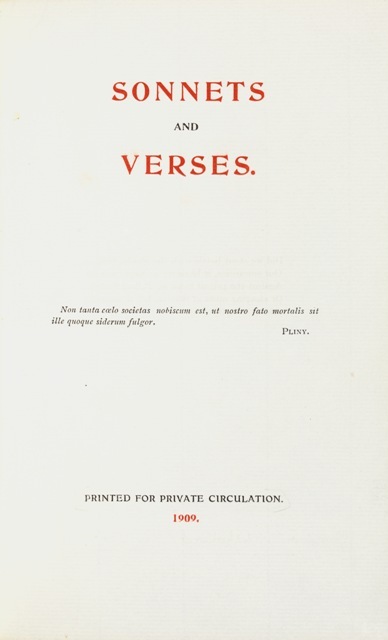

Sonnets and Verses

1909

Sassoon arranged for the printing of nine pamphlets of his verse and dramatic writing between 1906 and 1912. All were printed in small quantities, typically 35 or 50 copies, and in several cases later titles contained revised versions of poems which had appeared in earlier volumes. The young Sassoon was often quickly dissatisfied with his own productions, most notably in the case of Sonnets and Verses of 1909. The autograph note in the front of this exceedingly rare example records the destruction of most of the edition. This copy passed first to Sassoon’s Cambridge librarian friend Theo Bartholomew, from him to the collection of Geoffrey Keynes, and thence to the University Library.

Keynes.J.1.28

*

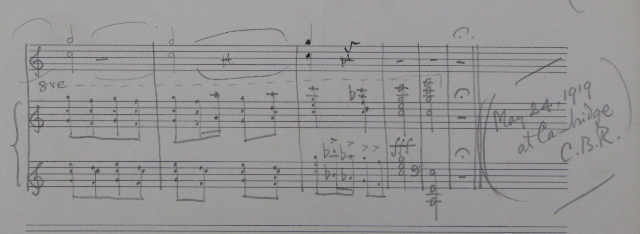

Hyacinth: An Idyll

1912

Hyacinth is a short play in prose, incorporating six poems, including this ‘Afterword’. It was printed for Sassoon by Charles Whittingham & Co. at the Chiswick Press, probably in an edition of 35. This copy was given by Sassoon to his friend Edward Dent, the Cambridge musicologist. The corrections to ‘Afterword’ are in Sassoon’s own handwriting.

Syn.7.91.43(1)

*

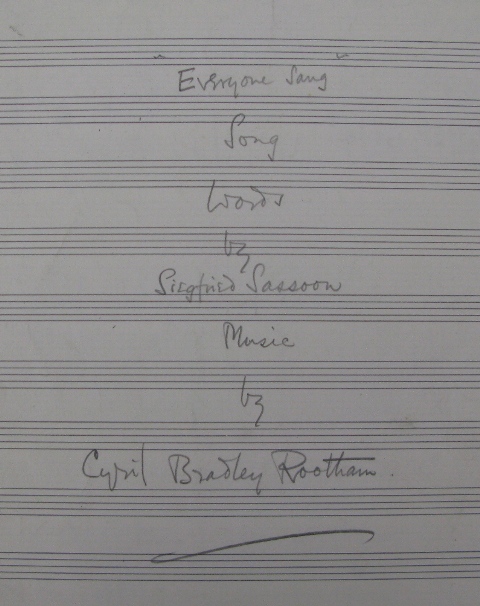

An Ode for Music

1912

The Antidote

No. 2, Vol. I, 1 February 1913

Opinions differ on the merits of An Ode to Music: Sassoon himself acknowledged its grandiosity, and his biographer Max Egremont calls it ‘Sonorously pompous’. Jean Moorcroft Wilson, on the other hand, writes of the ‘skill with which the difficult but rewarding form is handled’, and concludes that it has ‘more life and energy in it than most of his previous works’. Copies of the pamphlet sent to Edmund Gosse and Edward Elgar elicited no response, but T. C. Crosland, an early supporter of Sassoon’s writing, asked to be allowed to publish it in his periodical The Antidote, where it appeared in 1913.

Keynes.J.24(1–2)

*

The Daffodil Murderer: Being the Chantrey Prize Poem. By Saul Kain

1913

The Daffodil Murderer, written in December 1912, was a pastiche of John Masefield’s poem The Everlasting Mercy (‘Saul Kane’ was the name of the protagonist of that work). Despite, or because of, its derivative origins, it broke new ground for Sassoon as a poet: as he recounted in The Weald of Youth (1942), ‘I was really feeling what I wrote—and doing it not only with abundant delight but a sense of descriptive energy quite unlike anything I had experienced before’. ‘John Richmond Ltd’ was an imprint used by Crosland. The Chantrey Prize for Poetry was an invention.

From MS Add. 9852