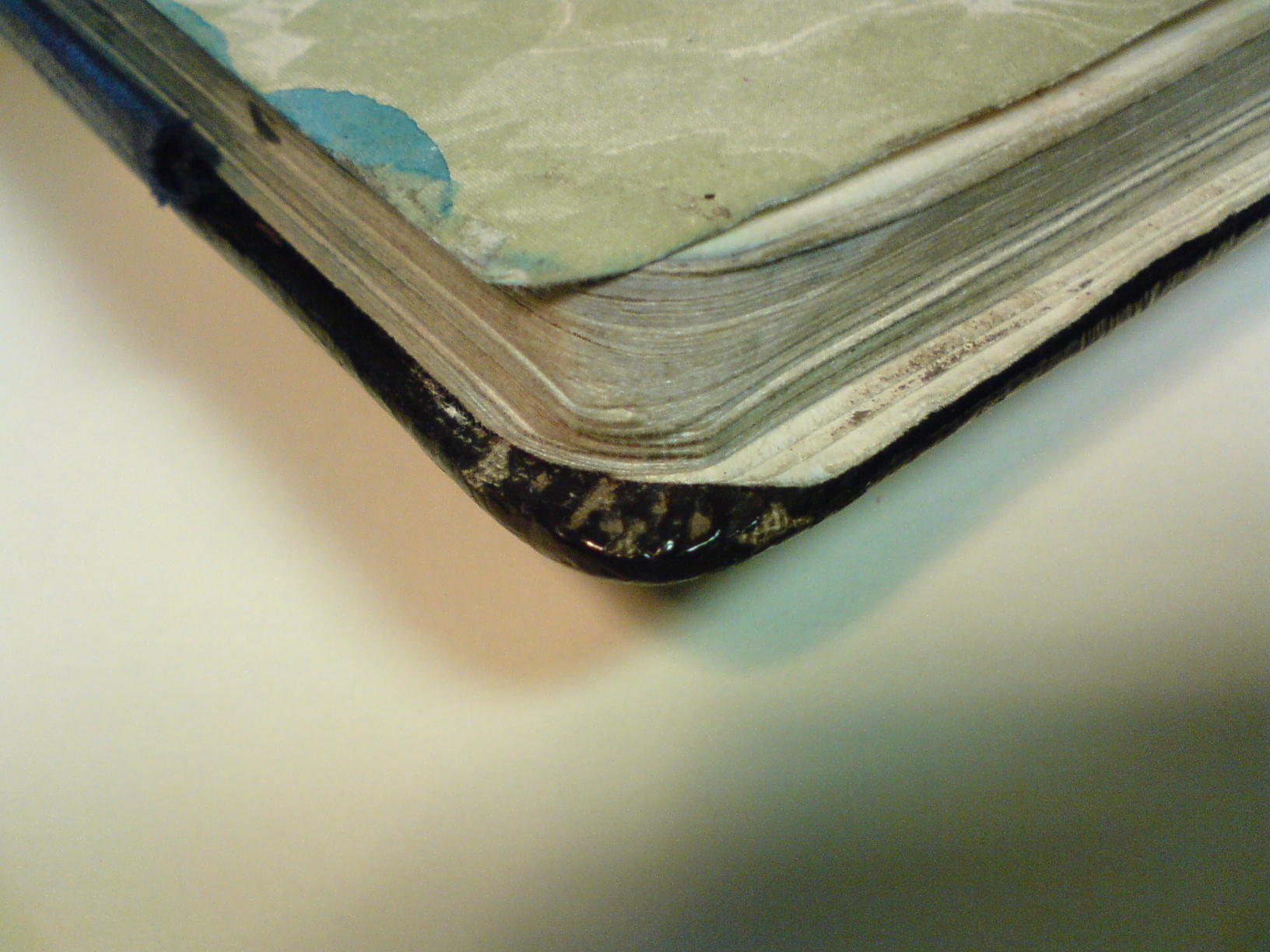

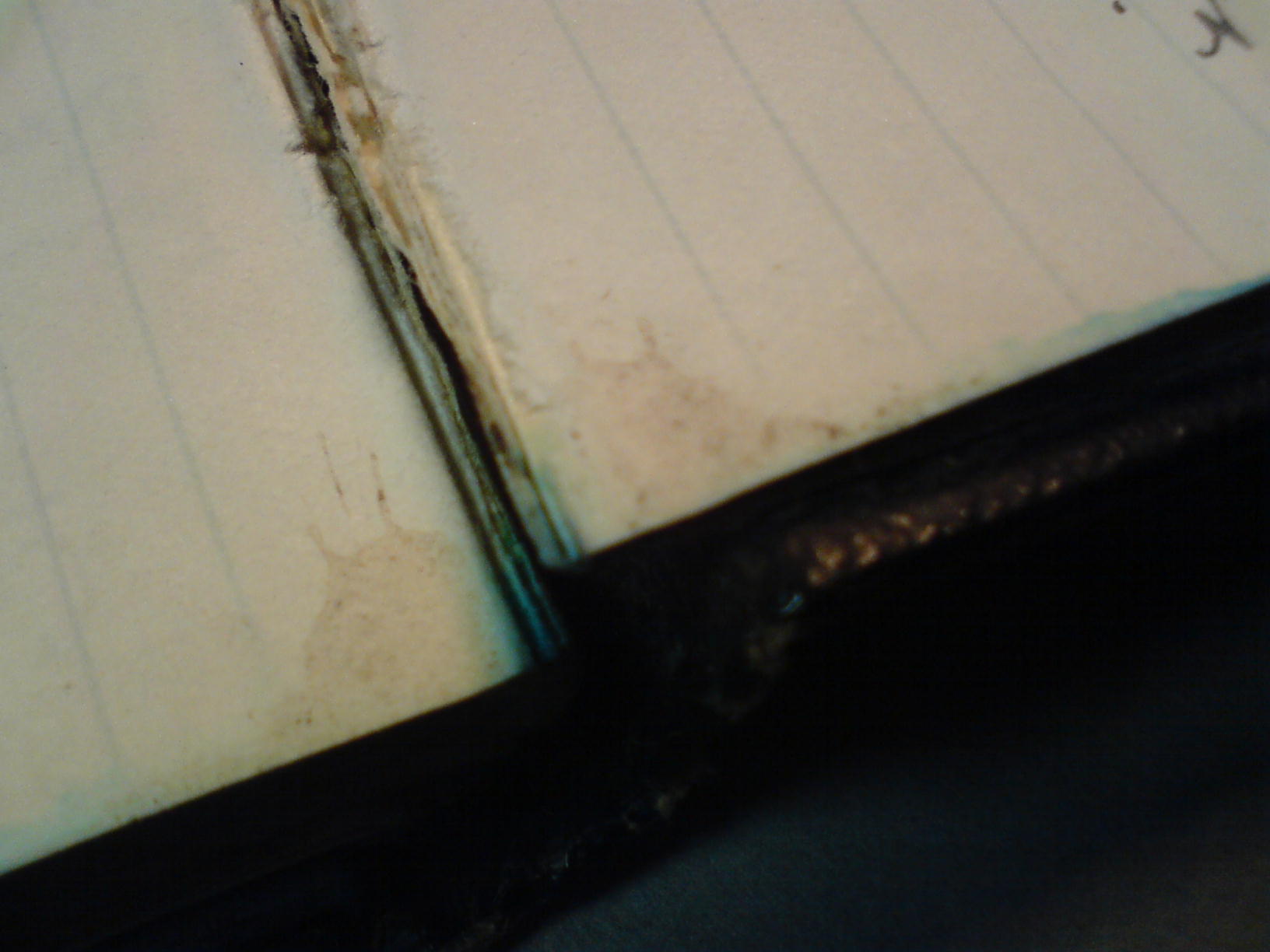

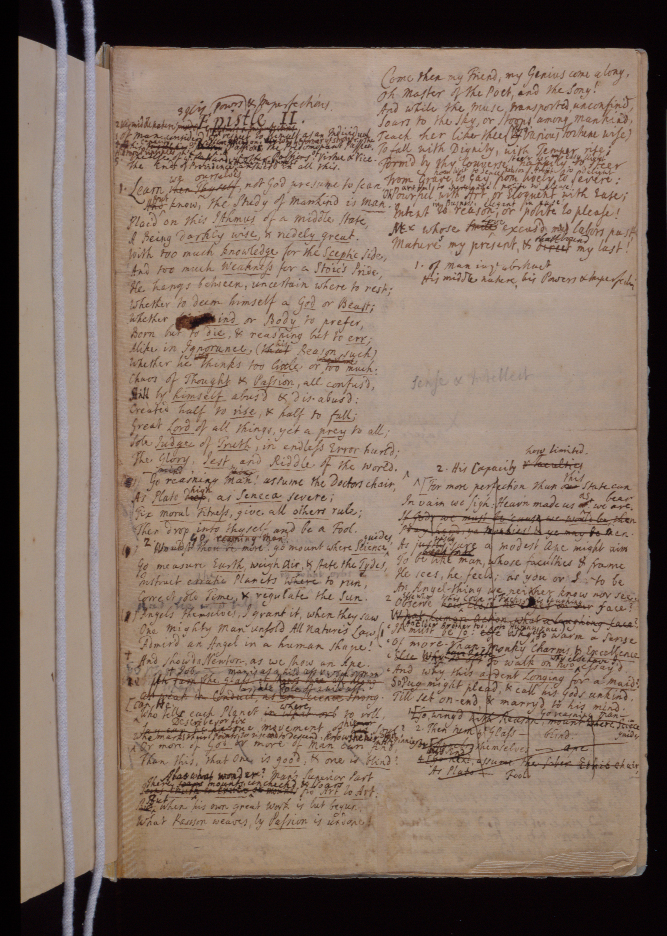

Late yesterday afternoon I finally found the much vaunted mud on the journal which Siegfried Sassoon was keeping at the time of the battle of the Somme. The ‘Dream Voices’ exhibition was dismounted on Tuesday and in the process of returning the items to their rightful places I spotted a volume that showed some signs of damp damage to the fore edge of the text block. Closer inspection also revealed dried mud:

Images of MS Add.9852/1/7

Click twice on an image for a zoomable version

I admit I had been sceptical about the reputed presence of trench mud. From what I can tell from the condition and content of Sassoon’s papers he was a neat and tidy sort of person. I had presumed that he would have cleaned up anything that had become soiled. The outside of the cover is made of cloth with a shiny finish and it would have been easy wipe. On the inside however attention to removing the mud appears far from meticulous. The mud is in the grooves around the inside cover of the notebook where the end papers overlap the covering on the boards and there are some ink bleeds at the edges of the pages.

Since the discovery, three questions have been bothering me:

Firstly, why is there so much interest, even excitement, about mud with regard to First World War archives and objects? Does the popular portrayal of the First World War somehow require the presence of mud on objects as a kind of validation?

Secondly, why have I found the presence of this mud particularly disturbing? This is interesting given the other macabre things that I have seen included in archives from time to time (e.g. teeth, hair, and bones both animal and human).

Thirdly, why did Sassoon not remove the mud?

Answers on a virtual postcard please…

On 28 January 1920 Siegfried Sassoon arrived by the Dutch liner Rotterdam into New York having been persuaded by lecture agent James B. Pond to deliver a lecture tour. On the 2 February Sassoon discovered that Pond had telegrammed to cancel the tour but had been thwarted by Sassoon taking an earlier ship than anticipated. The lecture tour circuit was suffering from ”English poet” saturation and only two lectures had been secured in February. Sassoon decided to remain in the U.S. and took on the onerous task of making speaking engagements himself. This was a troubled time for him for he did not feel he was a natural public speaker and he took his audience’s lack of basic factual knowledge about the war badly. His journal covering the tour period indicates he was deeply uncomfortable with the ”obscene publicity” and felt after reading his poetry to audiences ”as if my soul had been undressed in public”.

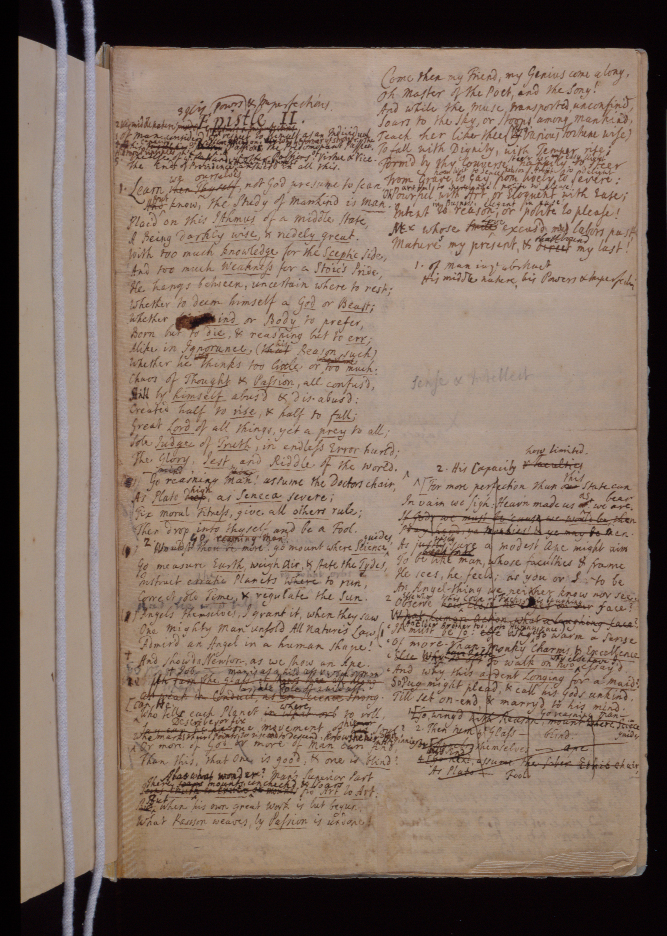

- Pope’s manuscript draft of his Essay on Man

Amid a chaos of travelling, speaking and dining with the great and the good he discovered a pleasing oasis of calm in the Pierpont Morgan Library, and found too a good friend in Librarian Miss Belle Greene. Here was an ”escape from the flurry and precipitancy of over engaged days”. In ”the little manuscript room … a sound-poof sanctuary” he saw Hardy and Keats manuscripts; and handled Alexander Pope’s draft of his poem An Essay on Man. The experience brought tears to his eyes.

The image of MS 348 in this blog post is used courtesy of the the Pierpont Morgan Library. Click on the image for a zoomable version of the document. Quotations are from MS.Add.9852/1/14 and Siegfried’s Journey (page 184-5).

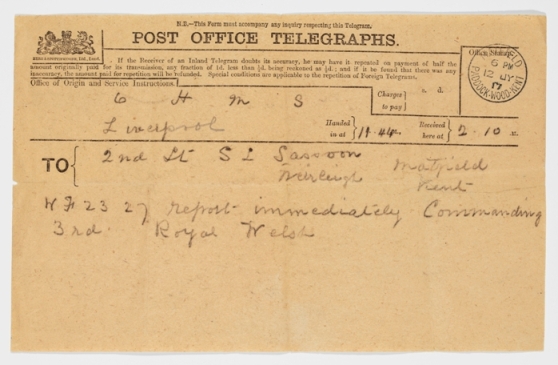

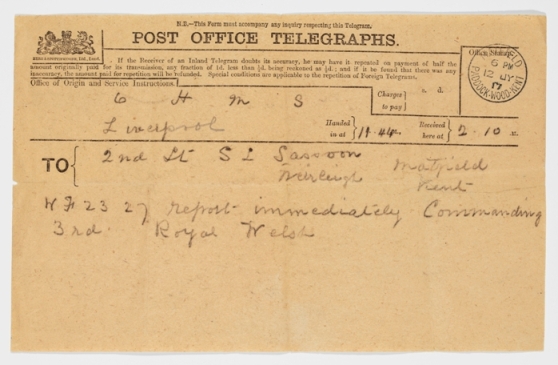

Telegram commanding Sassoon to report for duty found in the journal MS Add.9852/1/11

This terse telegram was sent to Sassoon on 12 July 1917 by his commanding officer in the wake of the publication of his ‘Soldiers Declaration’. Sassoon was deliberately overstaying sick leave permitted for recuperation from a bullet wound sustained at Arras. When Sassoon did indeed report to Litherland depot he fully expected, and in fact hoped for publicity’s sake, to be arrested and court-martialled. Instead he was directed to put up in the Exchange Hotel in nearby Liverpool to await further instruction. The government War Office, to whom the Army had referred the matter, were determined not to allow the statement to become a public cause. They, partially influenced by the intervention of various friends including Robert Graves, resolved the stand off by sending Sassoon to Craiglockhart Hospital near Edinburgh to recover from ”neurasthenia”or shell shock. At Craiglockhart Sassoon was to meet and nurture one Wilfred Owen.