Just what is it about trench mud?

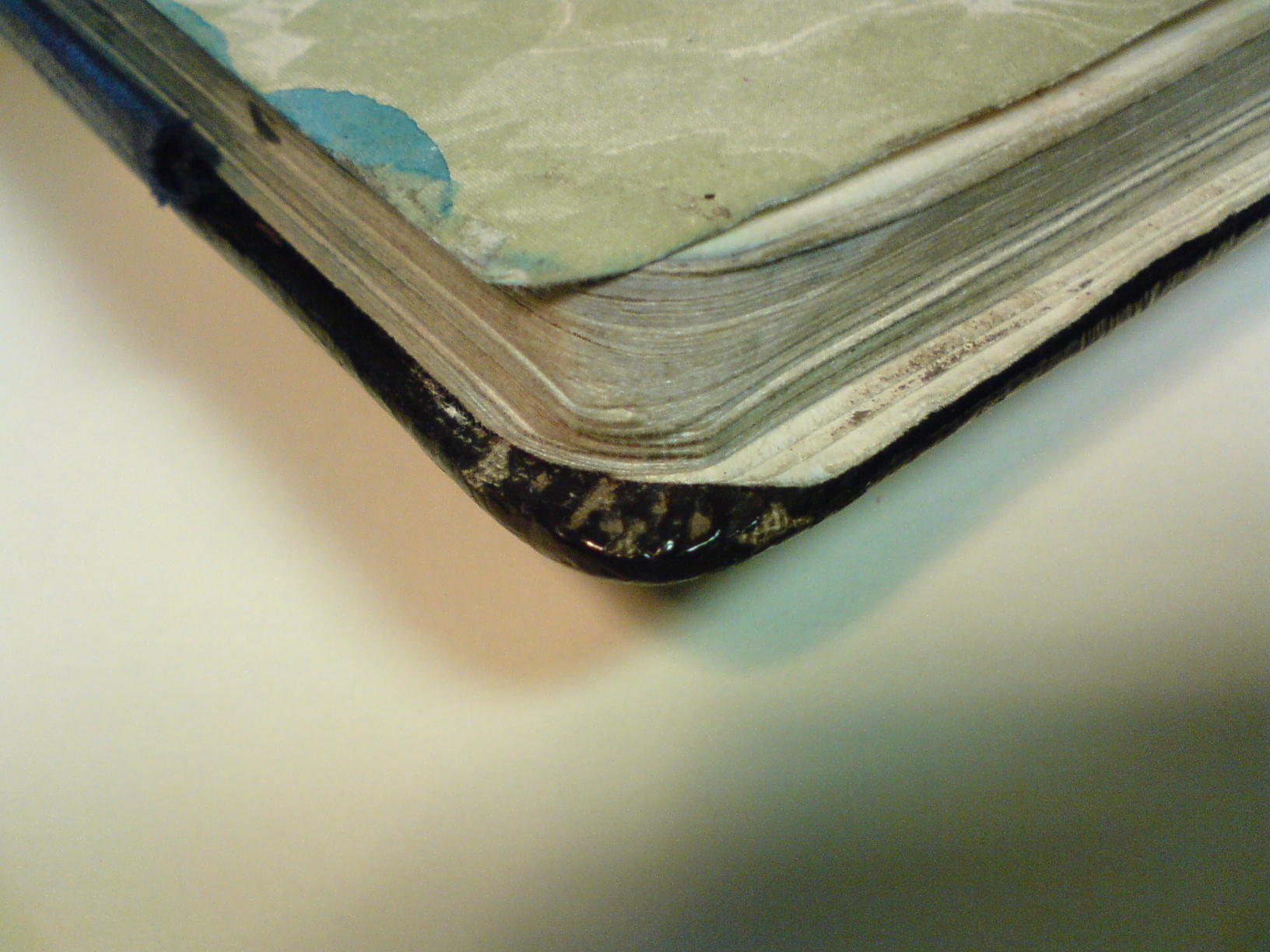

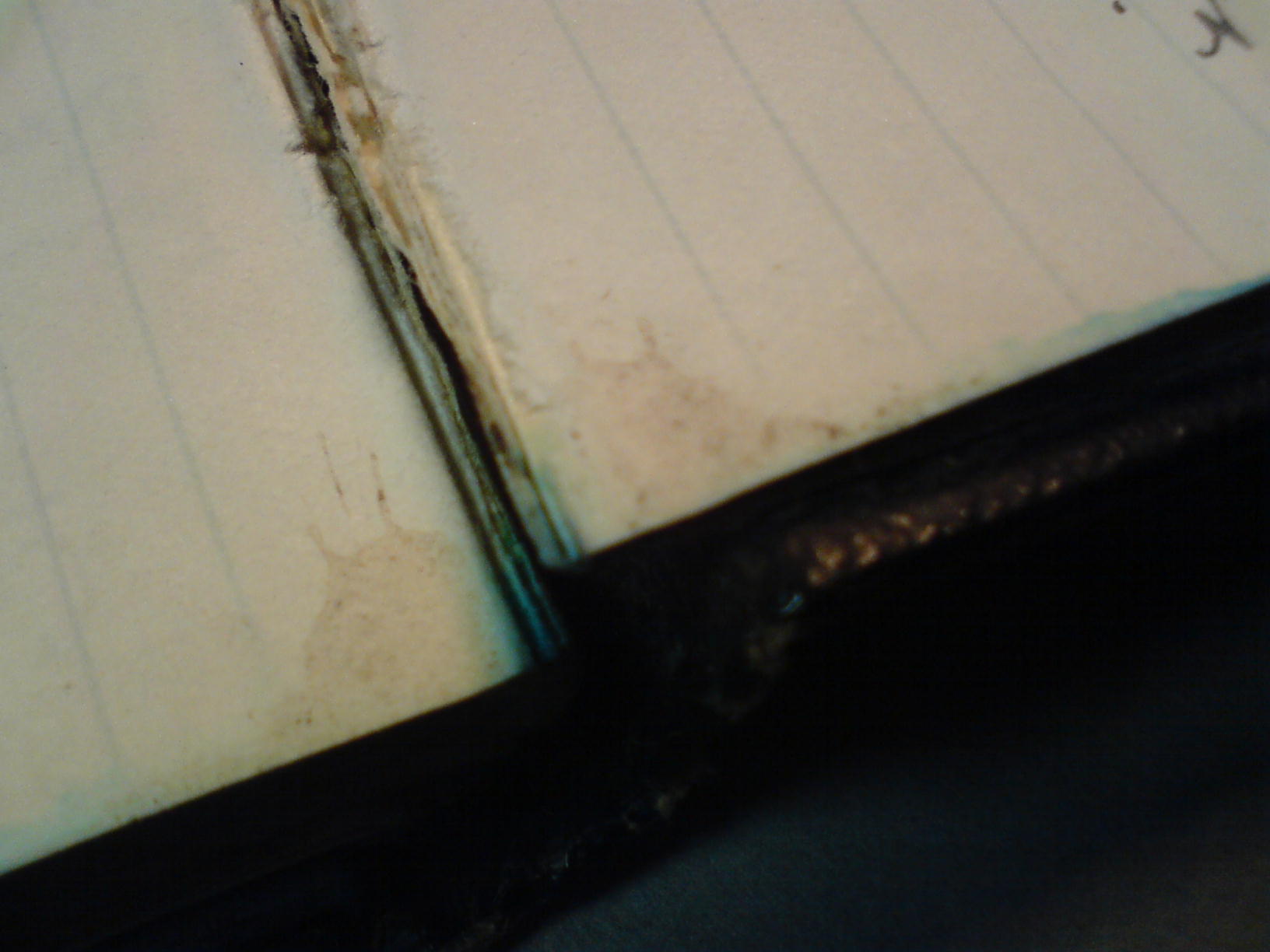

Late yesterday afternoon I finally found the much vaunted mud on the journal which Siegfried Sassoon was keeping at the time of the battle of the Somme. The ‘Dream Voices’ exhibition was dismounted on Tuesday and in the process of returning the items to their rightful places I spotted a volume that showed some signs of damp damage to the fore edge of the text block. Closer inspection also revealed dried mud:

Images of MS Add.9852/1/7

Click twice on an image for a zoomable version

I admit I had been sceptical about the reputed presence of trench mud. From what I can tell from the condition and content of Sassoon’s papers he was a neat and tidy sort of person. I had presumed that he would have cleaned up anything that had become soiled. The outside of the cover is made of cloth with a shiny finish and it would have been easy wipe. On the inside however attention to removing the mud appears far from meticulous. The mud is in the grooves around the inside cover of the notebook where the end papers overlap the covering on the boards and there are some ink bleeds at the edges of the pages.

Since the discovery, three questions have been bothering me:

Firstly, why is there so much interest, even excitement, about mud with regard to First World War archives and objects? Does the popular portrayal of the First World War somehow require the presence of mud on objects as a kind of validation?

Secondly, why have I found the presence of this mud particularly disturbing? This is interesting given the other macabre things that I have seen included in archives from time to time (e.g. teeth, hair, and bones both animal and human).

Thirdly, why did Sassoon not remove the mud?

Answers on a virtual postcard please…

Whilst I don’t share the apparent interest that some have in the presence contemporaneous mud, I think this discovery raises interesting curatorial issues. There’s every likelihood, as the notebook undergoes consultation by scholars, that the mud risks becoming dislodged – not through carelessness, but simply through normal (careful) handling. So, if the mud itself is an interesting, even valuable artefact, then it needs conserving somehow. It would be nice to think this can done leaving the mud in situ, although that might be incompatible with future use. Certainly a challenge for conservators. Not for the first time, we come up against the conflicting needs of “use” and “preservation” – in this instance I have a sense that the very existence of part of what makes this item interesting (i.e. the mud clinging to it) will impede the study of the notebook’s contents. What are the chances that everyone can be kept happy?

I feel even less qualified to suggest answers to your second and third questions, except that I would take some persuading that retention of the mud was a deliberate act on Sassoon’s part.

Having seen the document, I’m inclined to think that any mud that might be removed by “normal (careful) handling” would have come off during Sassoon’s lifetime. The traces that remain are mostly firmly lodged in grooves in the binding-leather caused by the material rucking as it was originally fitted around the corners of the boards. You would need a good stiff brush, or perhaps a pin or needle, to displace it now — and needless to say, implements of this kind are not approved for use by readers in the Manuscripts Room.

It strikes me that the ‘interest’, or ‘value’, of the mud can be thought of as analagous to Philip Larkin’s distinction between the ‘meaningful’ and the ‘magical’ value of manuscripts. Its evidential value for scholarship is minimal: presumably if it could be sampled in sufficient quantity then a soil scientist might be able to trace it to a particular locality, but the text of the diary is itself a fairly good guide to where the notebook has been (‘I am about 500 yds behind the front trenches, where Sandown Avenue joins Kingston road’, etc.), so not much would be gained by that. And yet I find it hard to think that anyone would prefer the mud not to be there. It is part of the document’s story, a mark of the circumstances of its existence over time, and a powerful component of its artefactual value — for some more ideas on this last matter see http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/exhibitions/writing_poetry/text_and_artefact.html

I wonder if part of the reason that you find the mud disturbing is precisely because it is linked to images of the First World War and particular to the horrors of the war (as opposed to the pathos and tragedy). There are, as you say, countless examples of archival collections which contain potentially far more gruesome items – Birmingham Archives and Heritage, for example, has part of a shroud (stuck next to a picture of a drawing of not very freshly disinterred body), suicide notes and then the usual collection of hair keepsakes and so forth which are, on the surface, more likley to provoke a reaction of disgust, revulsion or sadness. I think where things survive in a residual/accidental state – like the mud – they can be profoundly affecting. In our collections here in Birmingham, one that particularly sticks in ones mind albeit in a less upsetting context, is the bill from a chimney sweep from the late eighteenth century, covered in soot endorsed with a note to say “sorry the bill smells because my hands dirty”. I am relieved to report that the smell has since dissipated although it is still very dirty.